Photo by Kristina Jacinth

Click on the album cover to go to Kathy's review.

I recently reviewed a new album called

The Makrokosmos 50 Project by Nic Gerpe, an amazing pianist from Pasadena, CA. Also a faculty member at The Pasadena Conservatory of Music, Nic specializes in new music and has premiered the compositions of an impressive list of composers in concerts. As it is explained in the interview,

The Makrokosmos 50 Project is a celebration of the 50th anniversary of American composer George Crumb's (1929-2022)

Makrokosmos, Vol. 1, a set of twelve pieces that have had a major impact on Nic's musical life. The

Project includes Nic's performance of Crumb's original twelve pieces and then his performance of twelve new pieces by twelve different composers, including himself, that he commissioned. The

Project includes a

video presentation of all twenty-four pieces, which is as fascinating to watch as it is to listen to. In the course of writing my review, I found I had a number of questions about the music, so we decided to do an interview. I have learned so much from Nic Gerpe already, so I know you will enjoy getting to know him, too!

KP: Hi Nic! How is everything in Southern CA today?

NG: Hi Kathy! We are having a run of beautiful weather over the past few days, so I really have nothing to complain about (except lacking time to enjoy it at the beach...)

KP: I can really relate to that!

You recently released The Makrokosmos 50 Project, a monumental celebration of the 50th anniversary of George Crumb's Makrokosmos, Vol. 1, which was in response to Bela Bartok's Mikrokosmos. How did this project come about?

NG: Makrokosmos, Volume I is a piece that's been near and dear to me for many years. I first discovered Crumb's music as an undergraduate student at USC when my then-girlfriend (and now wife!) introduced me to a trio called Vox Balaenae - "The Voice Of the Whale" - for flute, cello and piano. It was such an amazing experience hearing this music for the first time, and I recall being absolutely blown away by Crumb's mystical, atmospheric, magical sound world, and his unconventional uses of all three instruments in that piece. I asked my teacher, Bernadene Blaha, if we could work on some of Crumb's solo music, and she assigned me Crumb's seven-movement work A Little Suite For Christmas, A.D. 1979. This piece was a revelation for me, and I really got hooked on Crumb's music as well as all of the possibilities of inside-the-piano playing techniques. Another inspirational moment for me was attending a recital by Dr. Stewart Gordon, who is another of the USC piano faculty. On his program was Makrokosmos, Volume I, and I knew after hearing his recital that I had to play this piece. Years later, as a Doctoral student, I told my teacher that I wanted to present Makrokosmos I as my lecture recital, and she arranged for me to study the piece for a semester with Dr. Gordon. Aside from being a consummate master of the piece, Dr. Gordon studied it with David Burge, who is the pianist that Crumb wrote the piece for initially. It was incredibly special to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Gordon, and all the moreso because of this connection back to Crumb. I performed the piece on a few more occasions - notably on my debut Piano Spheres recital in 2015 - and then put it aside for a future date. Early in 2021 I pulled the piece off the shelf again with the thought that I'd finally like to record it. It struck me as I was practicing it that the 50th anniversary of the composition of Makrokosmos I would be the following year. I had this idea to commission twelve composers (which ended up being eleven composers, plus me) to each write a response piece to one of the twelve movements of Makrokosmos I and create a new celestial cycle to celebrate the original.

KP: Is the Crumb work something you've performed often?

NG: Yes - I've performed Makrokosmos I many times in concert at this point. It's like an old friend. I've also played some of his other solo music, as well as his chamber works - the Four Nocturnes for Violin and Piano, Vox Balaenae for flute, cello and piano, and Makrokosmos III for two pianos and two percussionists are some of my favorites.

KP: What about the Bartok work that inspired Crumb? Have you performed it, too?

Photo by Brandon Rolle.

Photo by Isaac Schankler.

Photo by Brandon Rolle.

NG: Bartok is one of several composers that Crumb cites as inspirations for Makrokosmos I. The most immediate reference is in the title - Bartok composed his Mikrokosmos in six volumes, and they are teaching pieces of progressive difficulty. Mikrokosmos ends with the famous Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm, but there are many amazing little pieces in that collection. I think that there are lots of Bartokian elements to be found in Crumb - the use of the tritone as a structural device being an important one. As well, many of Bartok's innovations such as his development of "Night Music" appear in Crumb as well. When we think of "Night Music", we might think of the Nocturnes of Chopin or Field, which are lyrical pieces that have a contemplative, "nocturnal" sort of character. But when we hear Bartok's "night music" - whether in the piano solo suite Out of Doors, or his Fourth String Quartet, or in several of his orchestral works - we literally hear the music of the night. That is, atmospheric sounds, the chirping and calling of insects and night birds... literally a portrait in sound of being in the wilderness at night. Crumb also incorporates quotations of folk songs in his music, which is definitely something we remember Bartok for. I've performed several pieces from the Bartok's Mikrokosmos - they are really incredible miniatures.

KP: Is much of the Bartok work played from inside the piano, too? Or is it mainly on the keys?

NG: Actually, the Bartok is played entirely on the keys. There are a few pieces which utilize chord clusters, and at least one in Mikrokosmos which requires the pianist to silently depress certain keys on the keyboard while striking other keys, thus producing a glowing resonance. But that's about the extent of the "extended techniques" we find in the Bartok. Much of Crumb's inspiration for his various extended techniques comes from the music of John Cage and Henry Cowell.

KP: The Crumb work is in four volumes, and this one is Volume 1. Do you plan to do a similar celebration of all four volumes, or just this one?

NG: I'm definitely considering doing a similar celebration of Volume II - it's similar to Volume I in its structure and instrumentation. He wrote Volume II in 1973 as a follow-on to Volume I, and it features again twelve short movements for solo amplified piano. Crumb actually considered having the two volumes of twelve "fantasy pieces" as analogous to the two volumes of Preludes by Debussy - another composer who inspired Makrokosmos.

KP: Crumb's original work was subtitled Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac for Amplified Piano. Can you explain that a bit?

NG: Makrokosmos, Volume I, like much of Crumb's music, is absolutely loaded with extramusical associations. He cites the inspiration of Bela Bartok and Claude Debussy, as well as the "darker side of Chopin" and the "child-like fantasy of early Schumann". There are also two incredibly beautiful lines of poetry by Pascal and Rilke which Crumb quotes - "The eternal silence of infinite space terrifies me", and "And in the nights the heavy earth is falling down through all the stars into loneliness. We are all falling. And yet there is One who holds this falling endlessly, gently in His hands." Crumb also cites many big, cosmic concepts - "the timelessness of time, the problem of the origin of evil, the profound ironies of life expressed so eloquently by Mozart and Mahler." Each of the twelve movements of

Makrokosmos I (and later,

Volume II) is supposed to represent a different Zodiac sign, and is dedicated to a different person born under that sign - a colleague, friend, family member, teacher, or musical inspiration. If you look at the end of each movement, you'll see a set of initials. Crumb doesn't tell us who the initials stand for, so it's a fun mystery to try and figure out each person. The tenth movement of

Makrokosmos I - "Spring-Fire [Aries]" - has the initials D.R.B. at the end, which are the initials of David Burge. Movement 5, "The Phantom Gondolier [Scorpio]" has G.H.C., and is Crumb's own sign.

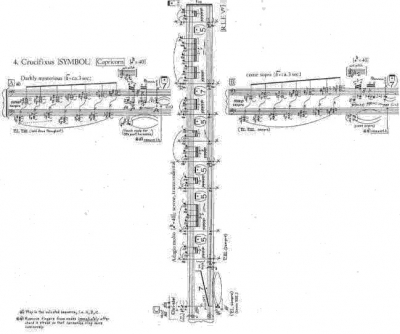

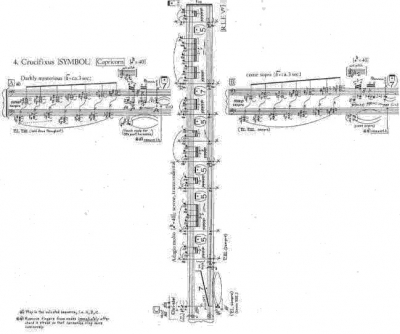

George Crumb, Makrokosmos, Volume I, Movement 4 - Crucifixus (SYMBOL) Capricorn

Copyright © 1974 by C.F. Peters Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission.

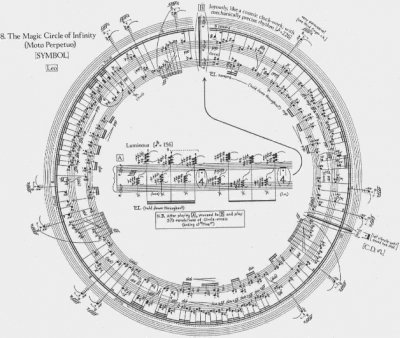

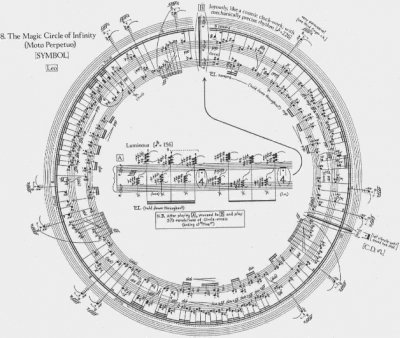

George Crumb, Makrokosmos, Volume I, Movement 8 - The Magic Circle of Infinity (SYMBOL) Leo

Copyright © 1974 by C.F. Peters Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission.

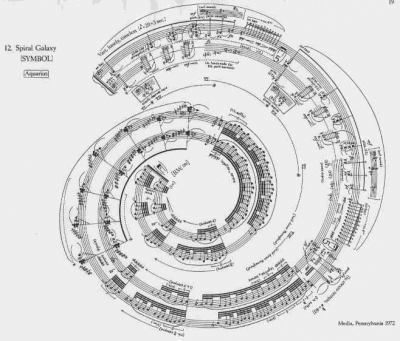

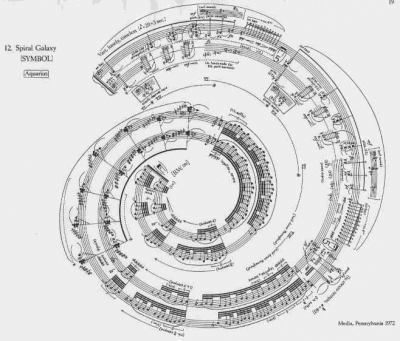

George Crumb, Makrokosmos, Volume I, Movement 12 - Spiral Galaxy (SYMBOL) Aquarius

Copyright © 1974 by C.F. Peters Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission.

KP: Technology has changed so much in the past 50 years. How was the piano "amplified" when Crumb composed the music, or was that process basically the same as it is today?

NG: For the amplification, Crumb says that "a conventional microphone (suspended over the bass strings) should be used for the amplification of the piano. The level of amplification should be set rather high so that the loudest passages are very powerful in effect. The level should not be adjusted during the performance." So at least for this piece, the process of amplification now is basically the same as it was 50 years ago.

KP: Interesting! On the album, the first half is the Crumb Makrokosmos, Volume 1, and the second half is your performance of twelve new pieces, each by a different composer (including yourself) as a response to each of the twelve parts of the Crumb work. How did you select the composers?

NG: Many of the composers are close friends of mine. Actually, the first composer who I commissioned was my wife, Juhi Bansal. After I had the idea to do this project, I asked her what she thought of it - she said "DO IT!" So of course I asked her immediately if she'd write a piece for me! After that, I asked several of my closest composer friends. One of the composers on my project I had met in the summer of 2021 and asked to write a piece after I had the opportunity to premiere a trio of his. Since I listen to a lot of new music and try to find composers who write for solo piano, I approached many composers whose music I love through the contact information on their websites and asked if they would be willing to write a piece for me. Several of them I had never known before or had the opportunity to work with. I was incredibly fortunate at how enthusiastic and supportive my composers were for this project, and I really could not have asked for a more amazing group of collaborators.

KP: How did you decide who was going to compose which pieces?

NG: I didn't! As I was asking the various composers to be a part of the project, I just told them to listen to the complete Crumb and select the movement that spoke to them the most.

KP: One of the things I appreciate most about the project is that you made a

high-resolution video of the full performance of all twenty-four pieces which is available on YouTube. I watched the whole video a couple of times and then wrote my review of the album while listening to the recording. Having seen the performance gave me a much deeper appreciation for and understanding of the music than I would have had with just the recording. Thank you for that! What gave you the idea to video the whole thing?

NG: Thank you so much for the kind words! Part of what makes Crumb's music such an amazing experience in concert is the theatricality and physicality of the performance. It's wonderful to listen to it through audio, but I have always felt like the visual element of the performance is almost equally important to the sound element.

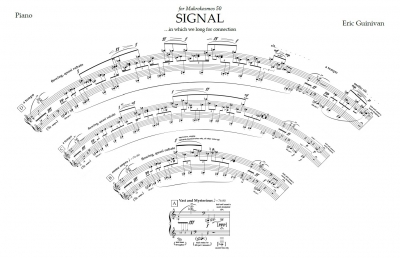

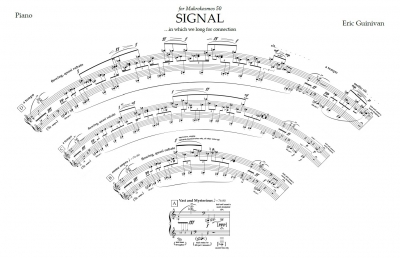

KP: I would have to whole-heartedly agree! On the video, you played the Crumb work from memory, but had a computer screen on the piano for most, if not all, of the new music. At times, the screen was viewable in the video, and some of the new music seemed to be written in a fairly traditional layout/format, but some pieces were notated in shapes. For example, Eric Guinivan’s "Signal," which is based on Crumb's "Crucifixus," is notated in the shape of the WiFi logo, "symbolizing our desire for connectedness with one another.” How do you approach playing something like that?

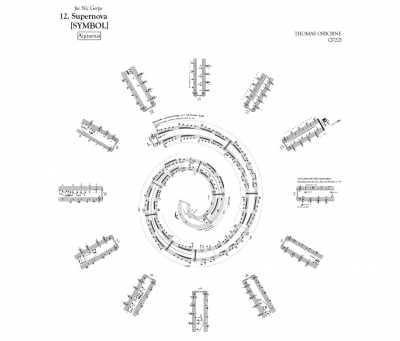

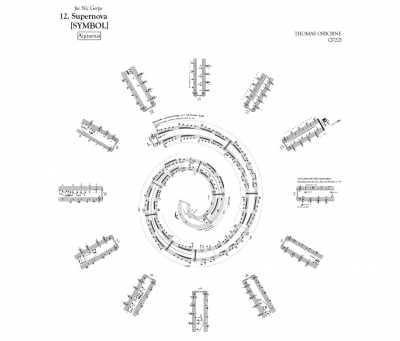

NG: Three of the new pieces had some kind of graphic score - incidentally, the three that were based on the graphic scores from Crumb. Eric Guinivan's "Signal", Julie Herndon's "Circle of", and Thomas Osborne's "Supernova". For the Guinivan piece, the curvature of the Wi-Fi logo is just slight enough that I can read it as a traditional piece. Julie Herndon utilizes some graphics to represent the waves of the electronic track that goes with the acoustic part of the movement, but is otherwise laid out as a traditional score. Thomas Osborne made a graphic score in the shape of an exploding star, which was also incredibly beautiful. Both Eric and Thomas were kind enough to provide me with the graphic score, and a performance score of the notes laid out in a traditional manner for ease of reading. For the Crumb graphic scores, I had to make my own performance/study versions by photocopying the originals, and getting creative with cutting/pasting (and not the electronic type!).

"Signal" by Eric Guinivan.

Used with permission from the composer.

"Supernova" by Thomas Osborne.

Used with permission from the composer.

KP: Wow! I've seen samples of some of Crumb's notation, and it really baffles me how you would approach playing it. How exacting is the sheet music? Is there much room for interpretation, or is it supposed to be played exactly as written?

NG: One of the things that I find so fascinating about Crumb's notation is how precise and clear it is. He always tells you exactly the sound he's after, and how to accomplish it. It's really precisely notated - for example, rests and fermatas are often notated in the exact number of seconds that they're to be held. He does say that these durations are approximate, as are the metronome indications. As well, articulations and dynamics are very precisely marked. Crumb's music is incredibly emotional and expressive, and there's definitely room for individual expression and interpretation as far as phrasing, color, etc. I'm reminded a bit of the quote from Alfred Brendel - "If I belong to a tradition, it is a tradition that makes the masterpiece tell the performer what to do, and not the performer telling the piece what it should be like, or the composer what he ought to have composed."

KP: That's a great quote! For those who are unfamiliar with this music, the pianist strums, picks, mutes and pounds the strings. Metal thimbles, a lightweight chain, and the soundboard are used to create even more of a variety of sound effects. The pianist also chants, whistles, and moans like a ghost. How much leeway does the performer have with all of that, or are you free to add your own interpretations?

NG: For most of the sound effects and extended techniques, Crumb is very precise as far as what pitches he wants. When he writes muted and plucked strings or harmonics, he tells you exactly the pitch he's after, and how to accomplish it - for example, he'll often ask for second and fifth partial harmonics (sounding one octave higher, and two octaves plus a third higher, respectively), and notates the key that is to be depressed as well as the resultant sound. Depending on the make and model of piano that you're playing, you may have to find an alternate string or key, but the resultant sound should be the same. For chord clusters, he gives the range of notes that are to be depressed, and whether the clusters are to be chromatic, white-key only or black-key only. In the "Phantom Gondolier" movement, where you play the strings with thimbles, he gives the exact pitches of the tune - the effect is almost that of an otherworldly zither.

KP: It seems like all of the playing inside the piano could be a little dangerous. Are broken strings and/or cracked soundboards a hazard? Does the piano need to be retuned during a performance?

Photo by Kristina Jacinth

NG: It's certainly possible to damage an instrument doing various inside-the-piano techniques, moreso for prepared piano (where you actually insert objects in between the strings). I've never heard of cracked soundboards being a problem, but you could certainly knock a piano out of regulation by accidentally hitting the hammers. The piano doesn't need to be retuned during a performance, any more than it would playing an intense recital of traditional music. Pianists who do this kind of music should be, and generally are, conscientious about doing it in a way that doesn't pose a risk to the instrument. There have been books written about this very topic - one that comes immediately to mind is Alan Shockley's The Contemporary Piano - A Performer and Composer's Guide to Techniques and Resources.

KP: I'm sure artists are very careful to not damage a piano, but it's fascinating to me that books have been written about the subject! Thanks for sharing that!

Now let's get to know you a little better. Where were you born and where did you grow up?

NG: I was born and raised in Pasadena, CA.

KP: Do you come from a musical family?

NG: Neither of my parents were professional musicians, but there was always music in the house. My Dad plays the guitar, and exposed me to all kinds of music when I was young - particularly classic rock, jazz fusion, and oldies. We'd constantly go to concerts when I was a kid, but I didn't really develop a major interest in classical music until my teens.

KP: How old were you when you started playing the piano?

NG: I was eight years old.

KP: How old were you when you wrote your first piece?

NG: I wrote a very short piece for piano when I was in the fifth grade, and then nothing until my Doctoral recital at USC for my electroacoustic music minor!

KP: Tell us a bit about your minor! This sounds interesting!

NG: One of my best friends, colleagues and mentors is a pianist named Aron Kallay. He's a huge force in the Los Angeles new music scene. While I was a Doctoral student at USC, Aron was teaching Electroacoustic Media - basically, playing repertoire using synthesizers and electronics in various forms. While studying with Aron, I learned how to use the computer program Logic, and we studied pieces which involve playing with electronics. Some of these works were for piano and fixed media - that is, a pre-recorded electronic part. You can think of it as playing with a tape, rather than as a second human player. Some of these pieces were for piano and live electronic processing, meaning that as you're playing your part, the computer is listening to your sound and manipulating it in real time. Often, you're required to trigger the computer to change processing patches during the course of a piece, so that it changes your sound in different ways. We also worked on microtonal music, and used synthesizers to re-program and re-map keyboards to play quarter tones, eighth tones, and all kinds of non-traditional tunings. I play music fairly regularly which involves electronics in some form or another. In fact, one of the response pieces on The Makrokosmos 50 Project - Julie Herndon's "Circle of" - involves a pre-recorded track. When she was composing the piece, she sent me just a few measures of music that she asked me to record myself playing. I sent her my recordings, and she used these as the basis for the electronic part of the piece, creating morphed swells and waves of sound. When I perform her piece, I'm playing an acoustic piano part with the electronic track as an accompaniment, or partner.

KP: Do you do much composing now?

NG: To be honest, the piece that I wrote for The Makrokosmos 50 Project was the only thing I've written since my electroacoustic recital at USC. It was almost purely on a whim - I thought I had this really cool idea for a companion piece to Crumb's "Phantom Gondolier" (Movement 5 from Makrokosmos I), and was tinkering around with some ideas at the keyboard anyway, so I figured - why not try writing a piece for my project? It's definitely inspired me to want to write more and I have some ideas for future pieces in mind.

KP: That sounds exciting! Where did you go to college?

NG: I did my undergraduate, Masters and DMA at the University of Southern California.

Photo by Brandon Rolle.

KP: You're on the faculty of Pasadena Conservatory of Music in Southern CA. How long have you been there and what do you teach?

NG: I've been on the Piano Faculty at PCM since 2006. I primarily teach individual piano lessons, although during the past few years I've also been teaching adult music history classes focusing on contemporary music, and I'm now co-curating a contemporary music series here.

KP: How many albums have you recorded?

NG: This is my first solo piano album! I've recorded individual pieces for albums by composers such as Gernot Wolfgang, Juhi Bansal, Erica Muhl and Jeffrey Holmes.

KP: Where are some of the places you've performed in concert?

NG: Some LA Venues: Walt Disney Concert Hall, REDCAT, The Wallis Annenberg Center for Performing Arts, LACMA, The Villa Aurora, Monk Space... Abroad, the University of Hawai'i at Manoa, the Banff Centre for the Arts, the San Francisco Center for New Music, and The Phoenix Concerts in New York.

KP: Who are some of your favorite composers?

NG: There are way too many to list! But I'd have to say some of my top favorites are George Crumb, John Corigliano and Kaija Saariaho.

KP: What do you like to do in your spare time?

NG: My wife and I love the outdoors - so we surf, hike, backpack and scuba dive.

KP: If you could have any three wishes, what would they be?

NG: More time, more time, and more time! And that tropical beach house would be nice.

KP: Indeed! Is there anything else you'd like to "talk" about?

NG: I'd like to thank you for giving me this opportunity to share my project with you and your readers!

KP: It's been a real pleasure, Nic!

Many thanks to Nic Gerpe for taking the time to do this interview! For more information about Nic and his projects, be sure to visit

his website, the Makrokosmos 50 Project website (https://makrokosmos50.com), and his

Artist Page here on MainlyPiano.com.

Kathy Parsons

April 2023